November 12, 2024

Small program, big vision: How the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is using and building evidence to move beyond crisis management in international wildlife conservation

By Dr. Daphne Carlson, Tatiana Hendrix, Dr. Matt Muir, Shannon Noelle Rivera, USFWS

The Division of International Conservation is striving to fund more of what works to conserve species abroad

Wildlife conservation faces a global crisis with the rapid loss of biodiversity, leading to calls for investing in the most effective conservation interventions. The wildlife sector has accomplished much utilizing the best available science, however, compared to other sectors such as medicine and public health, conservation science often lacks the data for rigorous evaluation and has a relatively short history of evidence and implementation science. There is a growing community of researchers, practitioners, and donors interested in learning and doing more of what works in conservation.

As a funder and implementer of conservation interventions, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has joined with other organizations to formalize our responsibility to embed evidence and learning in our funding decisions.1 Beyond fulfilling our conservation mission, we, as a Federal agency, have an imperative to responsibly steward taxpayer dollars. We are both conservationists and public servants and integrating learning and evidence into our programs will help us be better at both.

The USFWS’ Division of International Conservation is a small unit with a big vision, working in a relatively young and underdeveloped sector. How have we approached our learning journey? Our programs and staff are charged with making grants to implementing partners, the organizations and groups that carry out conservation work in the field, often under difficult and hazardous conditions. To target our limited resources to more of what works in these contexts, we have leaned heavily on partners and communities of practice in our network, including the federal evidence and evaluation community. We have benefited from guidance and advice from experts in other agencies, including the Office of Management and Budget. We have read and digested articles, presentations, and blogs written by others in this community and tried our best to adapt to our unique operating environment. We have built in accountability measures to keep us focused on our goal when the work gets overwhelming, and we have committed both human and financial resources to understanding and answering our most important learning questions.

Learning Culture

The USFWS is a bureau in the Department of the Interior (DOI). DOI is charged with protecting and managing the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage, and USFWS, working with others, is responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats domestically and internationally for the continuing benefit of the American people.

Savanna elephants in Tanzania. Credit: Matthew Luizza/USFWS

One of our first steps to build a culture of learning within our office (the Division of International Conservation within International Affairs) was to contribute to the DOI FY2022-2026 Learning Agenda with this priority learning question: What is the impact and effectiveness of our foreign species conservation assistance? Each year we report to DOI on our progress in answering this question and continue to refine our approach as we learn and adapt during our evidence journey. In addition, in 2024, our office became the first government agency to join Conservation Evidence’s Evidence Champion program. By signing on to this program, we commit to using relevant sources of scientific evidence in our processes, including, as applicable, the Conservation Evidence tool itself, which summarizes the evidence of effectiveness for conservation actions. Joining the Evidence Champion community also provides us with the opportunity to learn from and engage with the broader community similarly committed to embedding learning and evidence into conservation.

Assessing, Generating and Using Evidence

We have taken several steps to make better use of the evidence base available for the conservation interventions our programs support while encouraging the generation and use of evidence by the organizations that receive support through USFWS financial assistance:

Mountain gorillas in Central Africa. Credit: Dirck Byler/USFWS

- Identifying our most important learning questions: Using both a portfolio analysis and expert opinion, we identified priority conservation interventions to understand the current evidence base. Understanding the effectiveness of these key interventions will support decision making across our programs to improve conservation outcomes. The USFWS learning questions for our international work are captured in the Department of the Interior’s Learning Agenda.

- Building partnerships to assess the evidence: Since 2020, we have partnered with the Canadian Centre for Evidence Based Conservation (CEBC), one of six centers in the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence network. The CEBC provides expertise in evidence synthesis to support evidence-based decision making and policy making. Together, we navigate how to define our most important learning questions and identify which methods are best suited to answer those questions, including a range of approaches tailored to the state of the evidence in our field.

- Asking for evidence: Since 2023, each Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) from our office contains standard language that encourages applicants to justify funding requests with the best available evidence. In collaboration with other conservation funders and organizations, the USFWS is asking applicants of Federal funds for international conservation to demonstrate their proposals are based on the best available evidence. You can see this in action in our latest announcement, the Central Africa Regional Program Bushmeat Funding Opportunity, which focuses on reducing illegal bushmeat hunting and trade in Central Africa.

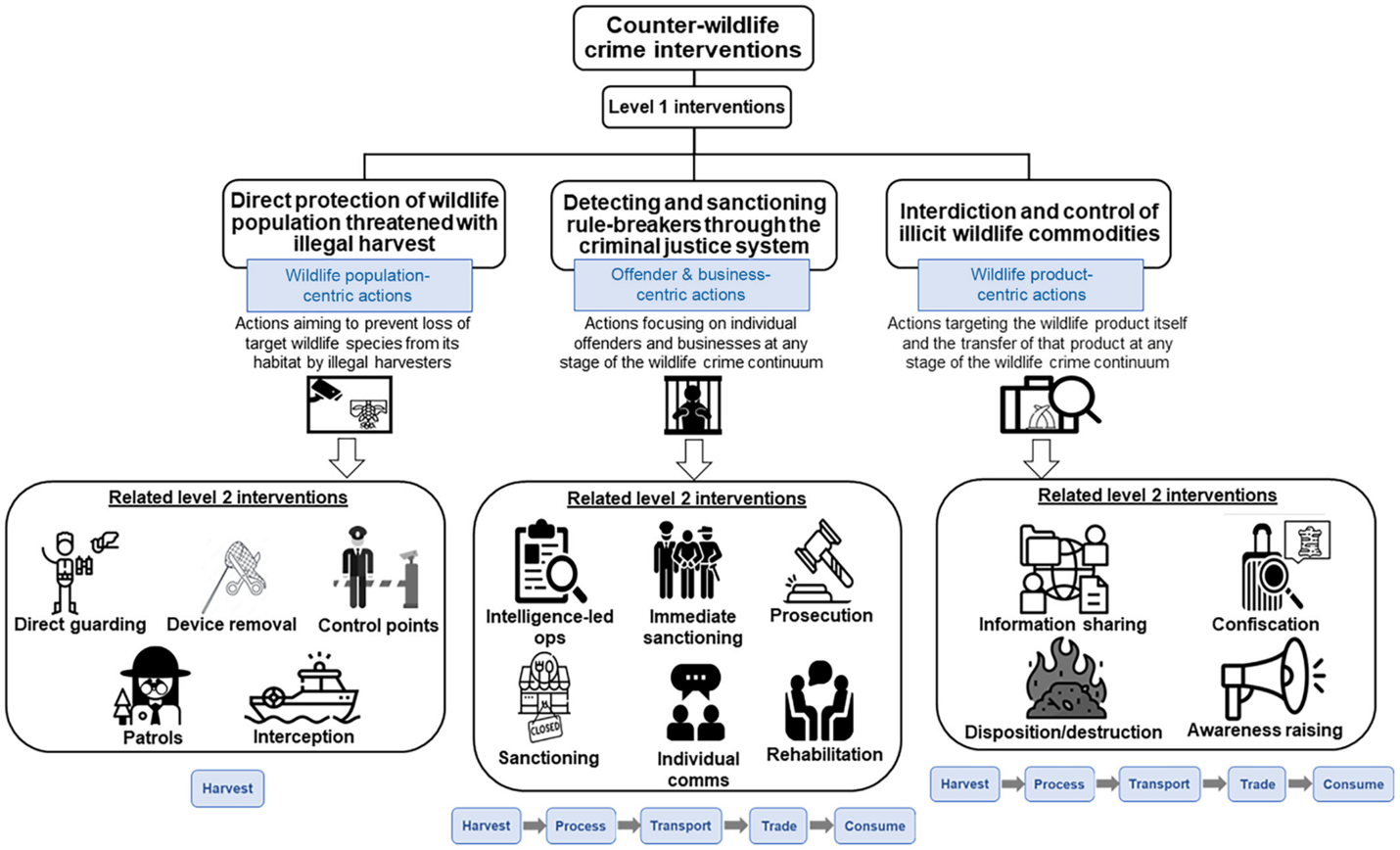

- Sharing our results: We are committed to transparently sharing our results with the broader conservation community so that all practitioners can benefit from our learning. This includes a commitment to publish our findings, like our recent evidence map on the effectiveness of counter-wildlife crime interventions, a powerful, data-driven tool that uncovered critical gaps in the evidence base.2 A recent paper in Conservation Biology explores how governance systems shape conservation outcomes providing new insights into how policies drive meaningful change.3

Visual from Rytwinski et al. (2024) What is the evidence that counter wildlife crime interventions are effective for conserving African, Asian and Latin American wildlife directly threatened by exploitation? A systematic map. The three eligible broad groups of counter-wildlife crime (CWC; level 1) interventions implemented to address wildlife crimes, their associated subcategories (level 2) interventions, and where these interventions fall along the wildlife crime continuum (bottom blue boxes).

Building the Evidence Base

In general, conservation programs are not designed and resourced in a way to collect data to assess effectiveness. We are currently considering how to best support the broader conservation community in building this evidence. We are simultaneously asking implementing partners to identify where new evidence is needed to determine effectiveness. We continue to explore the wide range of methods available to us, to promote evidence syntheses where sufficient research exists to support them, and to encourage consideration of other approaches, including how to appropriately incorporate Indigenous knowledge into our assessments.

Indian one-horned rhinoceros. Credit: Cory-Brown/USFWS

Concluding Thoughts

Conservation has been called a crisis discipline3 and often the urgency of threats on the ground have seemed to conflict with the need to build and use evidence to maximize the effectiveness of interventions. From our perspective, promoting learning and evidence-based conservation is necessary to advance our conservation mission and to fulfill our public service duties in stewarding our programs. With very limited human and financial resources, we have made a good start but recognize we have a long way to go. We always welcome interested partners in the evaluation community to join us on our learning journey. More broadly, we hope to support the use of evidence in the conservation community, including the continued development and use of new methods for conservation implementation science.

Tiger in Tadoba National Park, India. Credit: Cory Brown/USFWS

Learn More

The International Affairs Program (IA) within the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) coordinates domestic and international efforts to protect, restore, and enhance the world’s diverse wildlife and their habitats with a focus on species of international concern. Within IA, the Division of International Conservation stewards long-term and trusted grant-making programs, including the Multinational Species Conservation Funds, which provide support for on-the-ground conservation efforts to conserve elephants, apes, tigers, rhinoceroses, marine and freshwater turtles, and tortoises. The Division also houses landscape-level conservation programs for Central Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as a program focused on combating the illegal wildlife trade. Since 1990, the Division has obligated more than $230 million to implementing partners for conservation.

Dr. Daphne Carlson, Head, Division of International Conservation, USFWS

Tatiana Hendrix, Program Officer

Dr. Matt Muir, Program Evaluation Officer

Shannon Noelle Rivera, Program Evaluation Officer

1 Parks et al. (2022) Funding evidence-based conservation. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13991

2 Rytwinski et al. (2024) What is the evidence that counter wildlife crime interventions are effective for conserving African, Asian and Latin American wildlife directly threatened by exploitation? A systematic map. https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12323

3 Ayambire et al. (2024) Challenges in assessing the effects of environmental governance systems on conservation outcomes. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cobi.14392

4 Soulé, Michael E. “What Is Conservation Biology?” BioScience 35, no. 11 (1985): 727–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1310054

Tags: