January 23, 2024

Actionable Learning about Economic Recovery

By Jed Herrmann, U.S. Department of the Treasury

Summary: Treasury is using evidence to inform program implementation and is looking for opportunities to collaborate with researchers on evaluations (who can express interest by emailing OSPPI@Treasury.gov).

The U.S. Department of the Treasury recently released an updated Economic Recovery Learning Agenda. This learning agenda is designed to guide research by Treasury, other federal partners, external researchers, and state and local governments that received awards from Treasury to understand the impact of the country’s economic recovery programs on households, organizations, communities, and governments.

This economic recovery line of inquiry focuses on Treasury’s efforts to administer an efficient, effective, and equitable economic recovery for the country in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. As part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s response to the pandemic, Treasury’s Office of Capital Access (formerly known as the Office of Recovery Programs) is managing approximately $600 billion in programs aimed at helping state/local governments and communities respond to and recover from the pandemic. Many of these programs are completely new and thus present a great opportunity for research and learning to help with program implementation and consider how to design future programs. They also include large funding streams to support housing, broadband infrastructure, and small businesses.

Learning and Equity

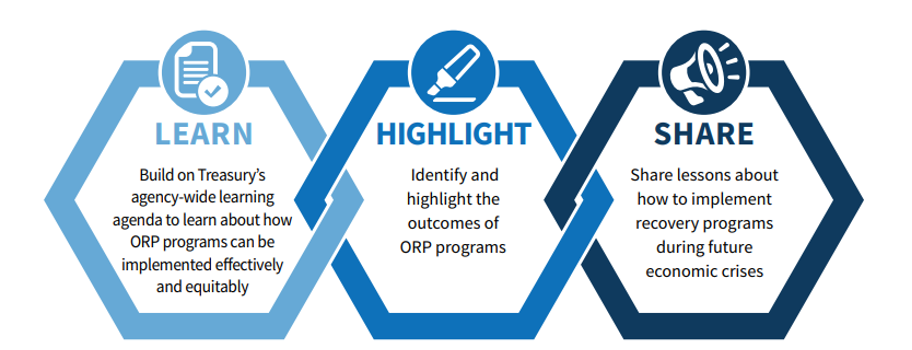

The Economic Recovery Learning Agenda is focused on continuous improvement in the implementation of federal economic programs and stems from Treasury’s first ever enterprise Learning Agenda, which was issued in 2022 and outlines learning priorities across five goals and 19 strategic objectives, including two high-level questions related to economic recovery that serve as the basis for the more in-depth Economic Recovery Learning Agenda. The Economic Recovery Learning Agenda aims to spur evidence building to help us learn about the effectiveness and equity of the programs, highlight the results we have seen, and share lessons learned that can be applied in the future.

Advancing equity is a major emphasis of the Administration’s economic policies with a focus on serving those households and communities that are most in need of assistance. Treasury’s evidence activities and the learning agenda are centrally focused on equity as an organizing principle.1 As such, the Economic Recovery Learning Agenda is premised on the idea that equity and outcomes are not mutually exclusive but rather inextricably linked—programs will not reach their true goals unless they are advancing more equitable outcomes.

Engaging Stakeholders to Refine Evaluation Priorities

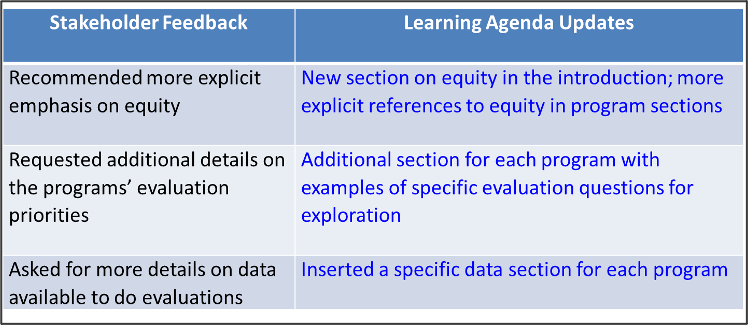

This updated Economic Recovery Learning Agenda incorporates changes based on extensive stakeholder engagement that Treasury conducted to receive feedback on a draft version released in spring 2023. To solicit this feedback, which was intended to make sure research priorities were informed and actionable by people outside of the federal government, we conducted approximately a dozen listening sessions, including both in-person and virtual. These sessions garnered a wide range of feedback from over 100 individuals and organizations, including state, local, and Tribal governments that received award funds, program beneficiaries, researchers, philanthropy, academics, think tanks, community organizations, government associations, members of the public, and other federal agencies.

In response to this feedback, the updated learning agenda contains more details on specific programs’ evaluation priorities, more information on the data available to conduct research, broader recognition of key stakeholders, and a greater emphasis on equity.

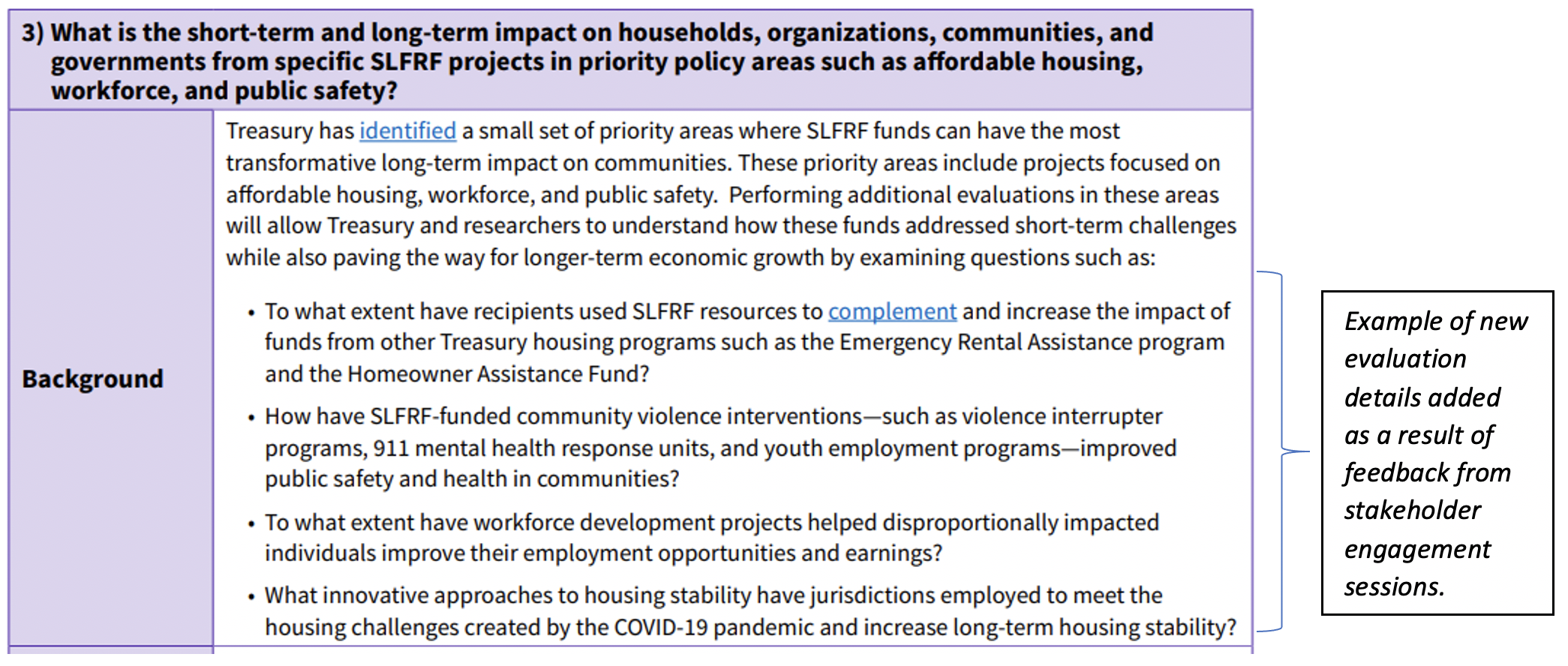

For example, the context and stories that we heard from people who have received assistance through these programs helped us to refine the evaluation questions in the learning agenda. As a result, we created a new section for each evaluation question (highlighted below) to capture more specific and actionable areas for research that would provide valuable information toward answering the overarching research questions.

We received many detailed responses that helped us refine the specific research questions for the programs administered by Treasury. For the Emergency Rental Assistance2 (ERA) program, for example, we included more opportunities for research about the role of landlords in the rental housing ecosystem. In particular, we included additional research questions on the distribution of rental assistance funds to different types of landlords, including landlords that own a small number of properties and often have similar demographics to the renters they serve.

This learning agenda is designed to be relevant for immediate program implementation as well as the longer-term view. The focus on both short-term implementation and long-term lessons means that we are interested in a variety of study designs, including:

In fact, Treasury has already used descriptive and process evaluations to make adjustments to a number of programs. For example, in the context of the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds program, we used a process evaluation to collect and analyze information about barriers facing very small localities and Tribal governments that received these funds, aimed at improving our efforts to help them comply with program requirements.

Collaboration to Build Evidence

A key part of Treasury’s approach to evaluation is engagement with external researchers. We have highlighted a dozen areas where we would be particularly interested in this engagement. In this regard, Treasury has posted two evidence portal opportunities for external collaboration here, on Evaluation.gov, for the Homeowner Assistance Fund program (question number 2 in the graphic below) and State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds program (question number 3 in the graphic below).

A sampling of questions from the learning agenda, highlighted in bold, where Treasury is interested in collaborating with researchers.

As an example of collaboration, Treasury has had a robust partnership with the Office of Evaluation Sciences on over 10 evaluations with a significant focus on using the results to inform program implementation. In addition, we are engaged with four research organizations to study the impact of the Emergency Rental Assistance program in coordination with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. As part of this collaboration, Treasury has shared detailed household-level data for these evaluations and is providing assistance to help researchers answer evaluation questions that are highlighted in our learning agenda.

By collaborating with outside experts, Treasury can learn lessons that will be valuable for future programs. These collaborations could consist of a variety of models, including program briefings and matchmaking between researchers and federal financial assistance recipients. As highlighted in the learning agenda, Treasury is already making an extensive amount of data publicly available but research collaborations could also potentially include additional data sharing. Researchers interested in collaborating with Treasury should send an email to us at OSPPI@Treasury.gov.

Applying Evidence to Inform Policy

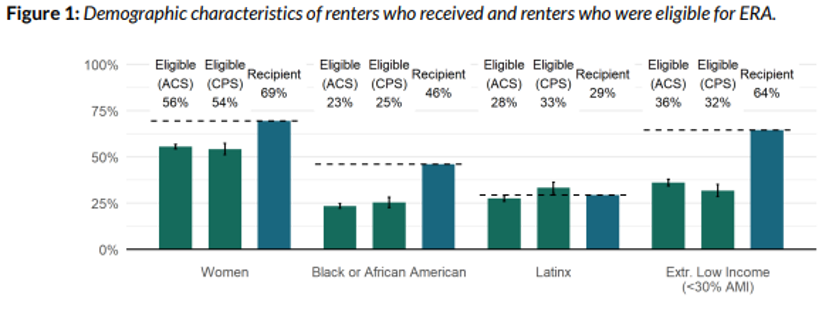

As an example of putting evidence into action, Treasury and the Office of Evaluation Sciences partnered to evaluate the equity of the Emergency Rental Assistance programs by examining how the demographics of renter households that received ERA assistance compare to the demographics of those renter households that are eligible to receive ERA assistance. Research conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic showed that Black renters and women renters represented a disproportionate share of those served with eviction filings. As such, Treasury focused on targeting outreach to these populations and working with ERA grantees to streamline the application process for ERA assistance to ensure that rental assistance reached those tenants most in need.

The evaluation found that Black renters and women renters were overrepresented among households that received rental assistance, across all regions of the U.S., and that funds were much more likely to reach “extremely low income” renters, or those whose households earn less than 30% of the area’s median income.

In this case, the study illuminated that Treasury’s efforts had generally been successful in reaching target populations that were most at risk of eviction. While the evaluation also found underrepresentation of White and Latinx renters, this was only at the higher end of the eligible income spectrum—extremely low-income White and Latinx renters were overrepresented among beneficiaries of ERA assistance, which reinforced the success of the program outreach efforts. However, Asian renters were moderately underrepresented at all income levels, which is consistent with their participation in other government benefit programs. Nonetheless, these findings led us to do subsequent outreach work to identify barriers for Asian tenants and make updates to better reach these populations.

A Virtuous Cycle

As illustrated above, Treasury is engaged across the full spectrum of evaluation from outlining priorities and conducting evaluations to using findings to inform program implementation. This virtuous cycle of applying evidence to practice is key to Treasury’s economic recovery work. Treasury’s approach is focused on using evaluation as a learning tool for improving program implementation and the design of future economic recovery programs.

Jed Herrmann is a Senior Advisor in the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Capital Access.

…

1 For the purposes of its work, Treasury defines equity according to Executive Order 13985, on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.

2 Two separate ERA programs have been established: the ERA1 program was authorized by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and provided $25 billion to assist eligible households with financial assistance and housing stability services. The ERA2 program was authorized by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and provides $21.55 billion to assist eligible households with financial assistance, provide housing stability services, and as applicable, to cover the costs for other affordable rental housing and eviction prevention activities.

Tags: